Search Results: why this, why you, why now

Create The Future You Want To See

The best investment I ever made in myself and my business was buying a copy of Seth Godin’s book, Purple Cow. Seth taught me that remarkability was a choice. Just as business owners don’t work just to pay the bills, writers don’t write just so they can eat. They write to create the change they want to see in the world. That’s what we’re all here to do.

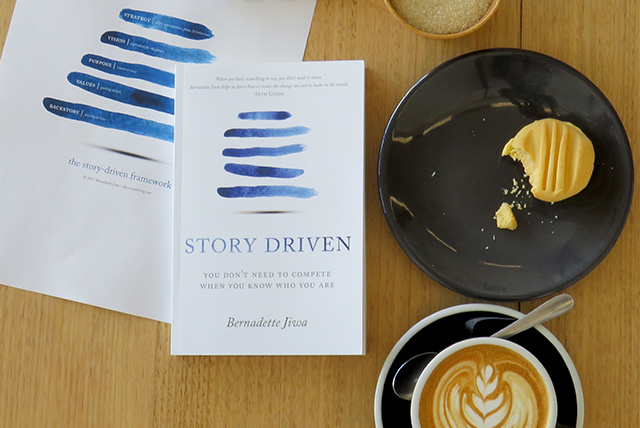

My new book, Story Driven: You don’t need to compete when you know who you are, published a few days ago. It’s my most important work. That’s why I’m launching the Kindle eBook edition at the special price of 99 cents this week. I’m not only inviting you to invest in yourself by buying a copy. I’m encouraging you to invest in your friends and colleagues by gifting the book to them.

You can buy and gift Story Driven today on Amazon.com, or if you’re in Australia, Amazon.com.au and the UK, Amazon.co.uk

(It’s available in all international Amazon stores. Search your local Amazon store by title and author).

We get to choose the future we want to see and the chance to create it together.

Thanks for giving me a reason to write.

Image by Kieran Jiwa

Why Do You Want To Tell A Good Brand Story?

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

Why do you want to get better at storytelling?

Why do you want to get better at storytelling?

When I ask clients and potential clients that question, I get a mixed bag of answers.

By far the most common reason is to increase brand awareness. Conventional wisdom argues that the more people who know about your product or service, the greater chance you have of selling more products and services. The simplest way to make everyone aware is to buy the attention of the most people. But the downside to that strategy is that you’re wasting resources speaking to people who have no interest in hearing or buying from you.

The second most common answer is to speed the process of attracting more customers. This mindset can lead business owners down the path of compromise, which presents its own unique set of challenges. You can’t do your best work when you start appealing to customers who don’t share your worldview. When you do, you attract the kind of customers your business is not designed to serve well.

Another reason commonly offered is to make sure to be seen in the right light by the right people. And while it’s smart to think about the audience you hope to engage with, you need to be mindful of telling a story that isn’t true just because it resonates with the people you’re speaking to.

Three Lessons From Great Brand Storytellers

1. Allocate resources where they have the most impact.

2. Get clear about the kind of customers you do and don’t want to attract.

3. Be as good at turning off the wrong customers as you are at attracting the right ones.

Your marketing motivations will ultimately inform your brand strategy and marketing tactics. That’s why it pays to know not just what you want to say and how best to say it, but also to understand why it’s important to you to say it at all.

Resonance begets belonging and belonging scales.

Image by rotesnichts

Why You Should Choose Your Customers

filed in Marketing, Storytelling

Marketing tactics often centre around finding customers for our products. We devote as much (sometimes more) time to generating enthusiasm for what we make, sell or serve as we do to making, selling and serving. It’s important to tell a story that resonates with the right customer. We do that by being clear about the worldview of the customer we want to attract.

Marketing tactics often centre around finding customers for our products. We devote as much (sometimes more) time to generating enthusiasm for what we make, sell or serve as we do to making, selling and serving. It’s important to tell a story that resonates with the right customer. We do that by being clear about the worldview of the customer we want to attract.

Choosing Your Customers:

- Allows you to be clear about the value you create.

- Gives you the opportunity to excel at serving the right people.

- Improves your marketing, sales and customer experience.

- Means you spend less time convincing customers and more time fulfilling their needs.

- Makes you more innovative because you see opportunities the generalist misses.

- Empowers you to build customer intimacy and loyalty.

- Helps you to become an expert in your field.

- Enables you to do your best work.

It’s as important to know who you’re not for as it is to understand the clients you would walk over hot coals to serve.

Image by Lennart Tange

Knowing What You Don’t Know

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

The most unhelpful assumption we make as marketers is that our customers know why they need our products or services. From there we think our job is to offer proof—to tell people why we are the best alternative. The first rule of innovation, sales and marketing is to understand the customer’s pain points (often before the customer knows them) and then to show her what life will be like in the presence of your product.

The most unhelpful assumption we make as marketers is that our customers know why they need our products or services. From there we think our job is to offer proof—to tell people why we are the best alternative. The first rule of innovation, sales and marketing is to understand the customer’s pain points (often before the customer knows them) and then to show her what life will be like in the presence of your product.

Your success is often determined by knowing what you don’t know about your customers, and by being aware of what they don’t grasp about their problems. Double down on understanding before offering proof.

Image by UN Women

Why Not Make Something Great?

filed in Storytelling, Strategy, Success

Like his grandfather, before him, Shane was in the textiles business. He made good socks for a living until the day he realised that pretty soon there would be no living to be made in a product that was good enough. His company was struggling to differentiate from and compete with big retailers who could manufacture and sell socks faster and cheaper. Shane realised their survival depended not on competing to make a comparable product only cheaper, but on understanding the customer who would be delighted by and pay more for the warmest socks in the world. Ten years on his business is thriving because he dared to rethink his business model.

Like his grandfather, before him, Shane was in the textiles business. He made good socks for a living until the day he realised that pretty soon there would be no living to be made in a product that was good enough. His company was struggling to differentiate from and compete with big retailers who could manufacture and sell socks faster and cheaper. Shane realised their survival depended not on competing to make a comparable product only cheaper, but on understanding the customer who would be delighted by and pay more for the warmest socks in the world. Ten years on his business is thriving because he dared to rethink his business model.

Without exception, whoever you are and wherever you’re reading this there’s one thing you have in common with every other person who is reading it too. You want your business or idea to succeed. You may not know exactly the path to that success, but you’re clear about the destination you want to reach.

Two things trip us up on the way to making our ideas matter. The first is our love affair with those ideas. The second is the fear of failure. In many cases, we’d rather press on uninformed and unenlightened than face the truth about the changes we may need to make to get to where we want to go. Because we invest so much of ourselves in our projects and businesses, the prospect of failure is painful. So we apply blinkers or look the other way hoping against hope that we were right all along. Blissful ignorance won’t help you to take your ideas from good enough to great.

The single biggest difference between a good product and a great one is the worldview and the posture of the person who created it. Instead of falling in love with their ideas they fall in love with their potential customers and users. They wonder what their customer cares about most. They look for problems to solve and unmet needs to fulfil. They strive to become indispensable by creating products and services that are not just useful, but meaningful. They’re not afraid to get it wrong because they know their missteps take them one step closer to getting it right.

We all have the potential to be that person if only we can lean into the doubts and dig deeper. That’s what I’m inviting you to do today. You can join me and other like-minded peers who are making their ideas matter by registering for The Story Strategy Course which starts on October 2nd. The course is self-paced, but you will have access to the platform and content as soon as you sign up, so you can get a head start. Be the exception. Take your idea from good to great.

Image of Fearless Girl by Shinya Suzuki

Why Your Business Needs A Set Piece Plan

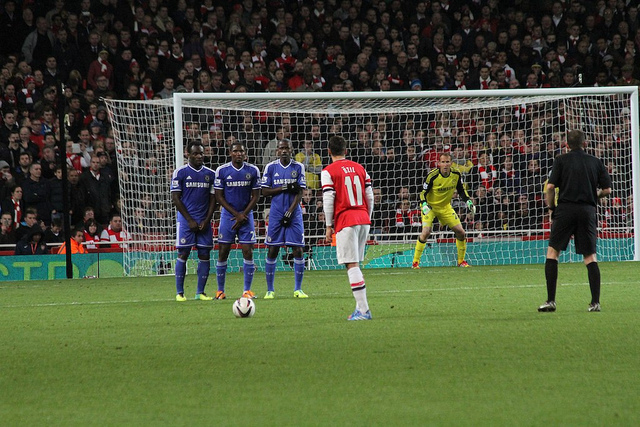

David Beckham scored 114 goals over the course of his 20-year football career. More than half of those goals were a result of what’s known as a ‘set piece’. A ‘set piece’ is a carefully orchestrated and practised move in a team game that returns the ball to play. Beckham became an outstanding player because of his dedication to rehearsing exactly what he would do when a particular situation arose in the game.

David Beckham scored 114 goals over the course of his 20-year football career. More than half of those goals were a result of what’s known as a ‘set piece’. A ‘set piece’ is a carefully orchestrated and practised move in a team game that returns the ball to play. Beckham became an outstanding player because of his dedication to rehearsing exactly what he would do when a particular situation arose in the game.

Having a ‘set piece’ plan can help us to excel in many areas of both business and life, but we rarely take advantage of it. Every day you experience average customer service that could be transformed with a ‘set piece’ plan. On Saturday when I was out to breakfast with my family we asked for a side of honey with our toast. The waiter said he would bring it right away. There was still no sign of the honey long after the toast was demolished. Of course, in the scheme of things the forgotten honey is a tiny thing, but those little things add up. They become the stuff of your brand story—the things customers remember (and share) about your business and the experience they had. The good news is it’s easy to create and implement a plan that fixes the problem so your service can be as consistent as David Beckham’s free kicks.

How To Create A Simple Set Piece Plan

1. Make a list of the most common customer service requests or interactions you’d like to improve.

2. Pinpoint the source of the disappointment.

3. Create a simple ‘if-then’ plan that details the ideal way to handle the situation.

- If a customer complains, first we do x, then we follow up with yz.

- If a customer knocks on the door five minutes before we open, then we…

- If we make a mistake with an order, then…

4. Assess how effective your ‘set piece’ plan is by measuring how empowered your team feels and also by monitoring customer satisfaction.

The brands that delight us anticipate and plan for what’s about to happen next long before it does.

Image by Ronnie MacDonald.

You Know More Than You Think

filed in Innovation, Strategy

We could be forgiven for thinking that facts and figures communicate the whole truth and hold the keys to unlocking the value in every future opportunity. New digital tools and technologies not only give us more information about the world around us and the people in it but also help us to know more about ourselves. We can literally monitor every step we take and every calorie we consume. The great hope is that if we can gather enough data, we will have the power to change the things we want to change—and that we can do it without having to face the fear of uncertainty.

We could be forgiven for thinking that facts and figures communicate the whole truth and hold the keys to unlocking the value in every future opportunity. New digital tools and technologies not only give us more information about the world around us and the people in it but also help us to know more about ourselves. We can literally monitor every step we take and every calorie we consume. The great hope is that if we can gather enough data, we will have the power to change the things we want to change—and that we can do it without having to face the fear of uncertainty.

Data—that which we can easily measure—is supposed to make us smarter, and maybe it can, but I’d argue that it doesn’t always make us wiser. Many of our actions and reactions can be observed and quantified, but that data doesn’t always expose the truth about why we take or have them. If it did, we would have found a way to stop people smoking cigarettes, overeating, gambling and drinking to excess. All of the health data that scientists use to persuade us to change our behaviour doesn’t necessarily have any effect. Hard facts tell only part of the story.

The Power Of Intuition In A Data-Driven World

Things are no different when it comes to evaluating the potential of ideas. Where was the data that predicted the need for and subsequent success of Google, Facebook and the iPhone, or the decline of Kodak, BlackBerry and orange juice? Which analyst forecast the 250 per cent increase in almond milk sales in the US over the past five years? Who anticipated that yoga pants would unseat jeans in popular culture, to spawn an active-wear revolution that will help the sports-apparel market be worth a predicted $178 billion globally by 2019? And what about colouring books for adults, with an estimated 12 million sold in 2015 in the US alone – who saw that juggernaut coming? When it comes to making predictions about which ideas will fly, we tend to forget that we can only use the information we have at hand about the past or the present to make a judgement call or prediction about the future. We don’t (or can’t) know the significance of things we have no information about, or haven’t yet thought to measure, and can’t possibly know for sure.

And yet we crave certainty, so we keep amassing and putting our faith in data. That faith has been fractured and then shattered by recent political events. According to Steve Lohr and Natasha Singer of The New York Times, all the data (and there was a lot of it) put Hillary Clinton’s chances of winning the 2016 US presidential election at between 70 and 99 per cent. As we know, these forecasts made by experts who had pored over every single possible data point turned out to be far from reliable. Lohr and Singer report ‘a far-reaching change across industries that have increasingly become obsessed with data, the value of it and the potential to mine it for cost-saving and profit-making insights’. However, they also remind us that, ‘data science is a technology advance with trade-offs. It can see things as never before, but also can be a blunt instrument, missing context and nuance.’ This proved to be true in the case of the 2016 presidential election. It was easy to measure how people said they would vote, but far harder to gauge what was in people’s hearts.

Not all of the useful information we can gather can be precisely measured and carefully graphed. What we observe in the everyday about what’s working and what’s not, why this is chosen, and that is rejected, and how the world still turns when people say one thing and do another, can lead to the seemingly insignificant insights that change everything. When we are creating ideas that will exist in the world, we must take that world into account—all of it, not just a logical, thin-sliced or convenient view of it.

We instinctively understand more than we give ourselves credit for and we didn’t learn it all from Britannica, Wikipedia or Google. Every day, we have access to vast amounts of information that we unconsciously collect. While this other kind of data is subjective, it’s still useful, and it can be put to work. If we train ourselves to become more observant, if we pay attention—to our surroundings, to other people, to what’s happening that shouldn’t be, or what’s not happening, that should be—our most mundane experiences can fuel our boldest and most brilliant ideas.

Excerpted from my new book Hunch: Turn Your Everyday Insights Into The Next Big Thing which goes on sale in the US today.

Image by Hernán Piñera.

Where Will Your Next Big Idea Come From?

filed in Innovation, Strategy

A few weeks before Hillary Clinton was defeated in the US presidental election I met a guy selling hats emblazoned with both candidates’ names outside the Rockerfeller Center in New York.

A few weeks before Hillary Clinton was defeated in the US presidental election I met a guy selling hats emblazoned with both candidates’ names outside the Rockerfeller Center in New York.

‘There will be a big upset in this election. Trump hats are selling like hotcakes,’ he said. It was hard to believe. Just the day before at a behavioural economics conference in Manhattan the academics and experts who had crunched every data point predicted exactly the opposite. The data showed Hillary was on track. But the sales in Trump hats didn’t lie. The data worth paying attention to was closer to home. It was in the stories of the people on the streets of towns where those who wrote the algorithms didn’t live and work.

In our digitally, data-stamped world, facts are king and intuition gets a bad rap. Author Michael Lewis describes the ‘powerful trend to mistrust human intuition and defer to algorithms’ that came about as a result of the work of scientists in the field of behavioural economics. The irony, of course, is that scientists too start out with nothing more than a hunch about what’s worth investigating further. Even those whose job it is to demonstrate proof start out not knowing for sure.

Things are no different when it comes to innovating in the commercial world. Where was the data that predicted the need for and subsequent success of Google, Facebook and the iPhone, or the decline of Kodak, BlackBerry and orange juice? Which analyst forecast the 250 per cent increase in almond milk sales in the US over the past five years? Who anticipated that yoga pants would unseat jeans in popular culture, to spawn an active-wear revolution that will help the sports-apparel market be worth a predicted $178 billion globally by 2019? And what about colouring books for adults, with an estimated 12 million sold in 2015 in the US alone – who saw that juggernaut coming? When it comes to making predictions about which ideas will fly, we tend to forget that we can only use the information we have at hand about the past or the present to make a judgement call or prediction about the future. We don’t (or can’t) know the significance of things we have no information about, or haven’t yet thought to measure, and can’t possibly know for sure. Data may be able to tell us what people do and how they do it, but critically, not why they do it.

Intuition, on the other hand, enables us to tap into our shared human experience to reveal a fundamental truth about what it is people want and need. Often there is no reliable data to go on—which is why the disposable nappy was invented by a frustrated mother, and Warby Parker was the brainchild of a guy who’d gone without glasses for a college semester because he couldn’t afford to replace the ones he’d lost. These stories of curious, empathetic and imaginative people who built successful businesses by seeing problems that were begging for a solution are retold over and over again. Successful entrepreneurs don’t wait for proof that their idea will work. They learn to trust their gut and go.

My new book Hunch: Turn Your Everyday Insights Into The Next Big Thing goes on sale in the UK and Australia today. If you’re in the US, you’ve got just a few more days to wait. Hunch will help you to harness the power of your intuition so you can recognise opportunities others miss and create the breakthrough idea the world is waiting for. Filled with success stories, reflection exercises and writing prompts, I hope it will be your guide to embracing your unique potential and discovering winning ideas.

What Are Your Customers Looking For?

We are sometimes in the dark about what our customers want, so we make assumptions or ask them in the hope of happening upon the truth. There is a third way to get closer to our customers—one we regularly overlook. People’s actions and reactions can reveal more about their internal dialogue than their words. When did you last spend time watching what your customers do?

We are sometimes in the dark about what our customers want, so we make assumptions or ask them in the hope of happening upon the truth. There is a third way to get closer to our customers—one we regularly overlook. People’s actions and reactions can reveal more about their internal dialogue than their words. When did you last spend time watching what your customers do?

As an author, I spend an unhealthy amount of time in bookstores. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve seen someone take a thick book from the shelf, feel the heft of it in their hand—then put it back. I can almost hear them thinking they’ll never get through it. Sometimes I get chatting to them and ask them what they’re looking for. Most of the time they don’t know.

Try this. Head down to your nearest department store, cafe, gym or wherever your customers are. Then stand back and watch what they do. Are they feeling garments before they check prices? Are they more likely to make a purchase if they’re alone or with someone? Are they looking for something specific? Do they compare prices with online retailers on their smartphone? Do they buy what they came in for? The list of questions, observations and potential insights are endless.

We tend to think of our customers as intentional, rational human beings—which is why we spend a lot of our time marketing to their heads. We make and market better products and services by working harder to get a glimpse of their hearts.

Image by mgstanton.

Where Does Your Story Start?

filed in Marketing, Storytelling

The easiest part of telling your story is writing it down. The hardest part is knowing what to say and why it’s important for your audience to hear. You must begin by wondering why someone (not everyone), will care about what you’re creating. That very act of questioning forces you to dig deeper and ask what you’re promising to whom. It invites you to get clear about why you wanted to make that particular promise in the first place.

The easiest part of telling your story is writing it down. The hardest part is knowing what to say and why it’s important for your audience to hear. You must begin by wondering why someone (not everyone), will care about what you’re creating. That very act of questioning forces you to dig deeper and ask what you’re promising to whom. It invites you to get clear about why you wanted to make that particular promise in the first place.

As marketers, we believe it’s our words that create value. But it’s the intention that informs the decisions guiding those words that delights and thus differentiates. Getting clear on that intention is where your story starts.

Image by David Bleasdale.