Unlock the Magic in Your Story Now

Get the Free 20 questions to Ask Before Launching Your Idea workbook when you sign up for occasional updates.

Get the Free 20 questions to Ask Before Launching Your Idea workbook when you sign up for occasional updates.

Articles filed in: Strategy

Better Than Maybe

The leaflet that dropped through my letterbox with the sleep clinic’s business card stapled to the front asked two questions.

Do you snore? Are you always tired during the day?

Inside, I’m told, sleep apnea, a disorder I may have, affects 20% of women. I might be one of them.

And therein lies this marketer’s problem. They know nothing about me, apart from the colour of my front door. Which means they have no idea if they should speak to me, nevermind what to say to me.

As marketers, if the best use of our resources is to only speak to the people who want to hear from us, then targeting every ‘maybe’ is not a great marketing strategy.

We can do better than maybe.

Image by Timothy Krause.

Memorable Marketing

In winter, when the real estate market is flat, and new listings are thin on the ground, Craig’s agency does letterbox drops offering free appraisals. Craig has no idea if this marketing tactic will work. But it’s worth a try. What has he got to lose?

And yet, when spring comes round, and he finally lists a property for sale, Craig barely makes eye contact with the people who come to view it. His job is to get enough people through to close the sale on auction day, then collect his commission.

What Craig’s overlooked is what he stands to gain by being remembered for the way he engaged with buyers, while advocating for his clients.

Memorable marketing isn’t just about what you say when—it’s about how you act at every moment.

Image by Paul Wilkinson

One Chance

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

If you could tell your ideal customer just one thing about your product, what would you tell them?

What would you change about your service if you knew you only had one chance to woo that customer?

How would things be different and better if we acted as if every chance to do the right thing was our first, last or only one?

Image by Jonalyn

Why Next?

My uncle Larry taught me to play chess when I was eight or nine. I learned just enough rules to get started because he said I’d learn how to play, by playing. The thing I’ll always remember is the way he taught me to make better moves. Every time I picked up a piece to move it he’d ask, ‘Why is this your next, best move?’

We’re all good at asking the question, ‘What next?’

In our impatience to make progress, we’ve become experts at looking for the next, new thing that will bring us more of whatever we’re after — more opportunity or more influence, more joy or more money—not necessarily in that order.

But we’re not so good and questioning, ‘Why next?’

We make more right moves when we reflect on how the next thing we’re about to do aligns with our values, and if it’s helping us to get to where we ultimately want to go.

Image by Kurt Bauschardt

Soft Metrics

Traditionally, we measure performance through the narrow lens of hard data.

Sales, profit and cash flow are seen as reliable indicators of how well we’re doing.

But hard data alone paint a two-dimensional picture of success.

There’s nothing to stop us prioritising outcomes we care about, but can’t reliably measure.

We don’t have to forsake ethics for profitability.

We can simultaneously pursue growth and generosity.

What we measure gets managed. And what we manage is the making of us.

Image by neonbrand

Reaching Resonance

filed in Marketing, Story Skills, Strategy

Many of us spend the majority of our time thinking about what people want to hear.

And while it’s important to understand your audience, it’s equally important to remember what you have to say, as only you can say it.

Of course, you want to make a bigger impact and reach more people.

But the impact you make will depend on your ideas resonating with the right people—not just reaching the most people. The people who believe in you and your message will enable you to do your best work. You will draw those people to you by clearly making your assertion and stating your intention.

It’s a lot easier to tell true stories over time than it is to keep coming up with new and interesting angles.

What’s the truth you want your audience to know?

Image by Jeremy Bishop

The Power Of Describing The Problem

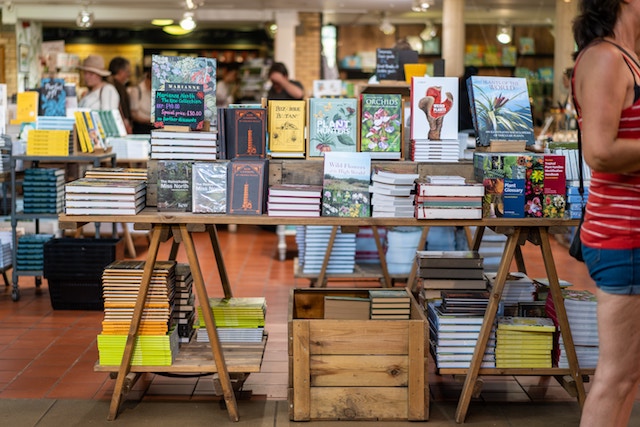

Four hundred Barnes & Noble bookstores have closed since 1997. In the last five years, the chain has lost a billion dollars in market value. But it seems hope is on the horizon. The private equity firm that owns the UK bookseller Waterstones recently bought the company. Waterstones CEO, James Daunt, will move to New York to begin his new role as chief executive of the struggling bookseller.

Mr Daunt has a challenging—some might say, daunting task ahead of him. Where should he begin? Well, it turns out that he chose to begin by describing the problem.

Daunt was quoted in the New York Times as framing the problem like this:

“Frankly, at the moment you want to love Barnes & Noble, but when you leave the store you feel mildly betrayed. Not massively, but mildly. It’s a bit ugly — there’s piles of crap around the place. It all feels a bit unloved, the booksellers look a bit miserable,

it’s all a bit run down.”

We often dwell on the symptoms of the problem, instead of the possible causes. Booksellers could lament that people prefer to shop online or that they browse and don’t buy instore. Symptoms, not causes.

It’s tempting to jump ahead to creating solutions before describing the root of the problem. But we can’t we begin to have honest conversations about how to solve problems before we own them.

Image by Rumman Amin

The Role Of Rules

filed in Strategy

You don’t need to produce photo ID in Australia to vote. But the manager at our local post office will never, and I mean never, under any circumstances, give you the parcel you’ve come to collect unless you have photo ID. The result is he turns away more disgruntled customers than he serves happy ones.

The guy is just doing his job. The rules are the rules. But the question is, why these rules? Who do these rules best serve? What proportion of parcels awaiting collection are handed over to an imposter?

It’s worth checking if the rules we hold dear, and fast to are helping the people we serve.

Rules Checklist

- Why does this rule exist?

- Does this rule benefit the majority of our customers? How?

- Do we have difficulty looking people in the eye when we explain this rule? Why?

- What story does this rule tell the customer about our values?

- How does this rule make us better?

- What would happen if we scrapped this rule?

Doing what’s accepted or expected isn’t necessarily the right thing to do.

Image by Markus Spiske

Who Do You Want To Be To Whom?

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

Our local organic shop is dying. When it first opened, it stocked things health-conscious shoppers couldn’t get anywhere else. Organic vegetables, vegan and gluten-free products weren’t readily available in supermarkets. There wasn’t enough demand for coconut oil and buckwheat flour for supermarkets to stock them. But as we all know, a shift in awareness and worldviews about health and wellbeing has changed that.

As the shelves of organic produce in the big supermarkets expanded, the range of products at the local organic shop contracted. The first things to go when customers started to defect to supermarkets were things that seemed non-essential— the things that differentiated the local store and gave people a reason to come. Knowledgeable staff, free product tastings and community events. Flowers and plants for sale out front. All that went by the wayside. The in-house cafe hours were cut too.

Locals want to support the little guy. But it’s hard to justify a price difference of three dollars on a single item. The local shop isn’t more convenient than the big supermarkets, and it can’t compete on price, but it can provide an experience that’s head and shoulders above the big supermarket. If people don’t have a reason to come, then they’ll pick up their organic oats in the cereal aisle next to the Cheerios at one of the big supermarkets. The customer experience was that reason.

The key question for the owner is not how to compete—but who do we want to be to whom?

That’s the key question for all of us, no matter what business we’re in. When we lose sight of who we’re in business to serve, and why, we lose more than our competitive advantage. We lose the heart and soul of our business.

Image by Dan DeAlmeida