Unlock the Magic in Your Story Now

Get the Free 20 questions to Ask Before Launching Your Idea workbook when you sign up for occasional updates.

Get the Free 20 questions to Ask Before Launching Your Idea workbook when you sign up for occasional updates.

Articles filed in: Storytelling

What’s At Stake For Your Customer?

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

We often use customer insights to inform product and service development. Throughout the process, our goal is always to empathise with the customer. But sometimes the language we use stops us from achieving that goal. For example, it’s harder to imagine a particular person with a problem by making a list of customer ‘pain points’, than it is to think about what’s wearing a customer down.

For example, we might list the pain points of someone (like my mum), who has trouble opening jars with her arthritic hands, as impaired grip, limited mobility and so on. But we form a more complete picture when we do the work of understanding the impact of those pain points. We get a sense of the emotional cost of living with those pain points when we think about what’s at stake for the person we want to serve.

Here’s how this works in practice.

Two Customer Insights Exercises

Exercise A. Make a list of your customers’ frustrations.

Exercise B. Stand in one customer’s shoes and fill in the blanks in the following sentences.

I’m tired of doing [X] and not achieving [Y].

I’m tired of feeling [X] and never being [Y].

I’m tired of being [X] and not doing [Y].

I’m tired of saying [X] and never getting to [Y].

When we do exercise B, instead of a list of pain points, we get an understanding of the customer’s story and her internal narrative. “I’m tired of having to ask for help and not being able to cook properly because I can’t open jars. When I can’t open a jar I feel like I’m getting weaker and losing my independence.”

What’s your customer’s story?

How does your product or service help your customer do less of X and experience more of Y?

That’s the story your customer wants and needs to hear.

Image by Kirsty Andrews

Fact Or Fiction?

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

The bookstore in Albert Park had just opened when Thomas, dressed as Batman, and his mum walked in. They headed straight to the children’s section at the back. They were shopping for a present for Ben, who was having a superhero birthday party that afternoon.

‘Let’s get Ben this book about Brazil. Then he can learn all about the people in Brazil,’ Mum said.

‘No! I want to get him a book about Batman,’ Thomas shot back, bottom lip out and cape askew.

In the end, they bought both books, but you can guess which one Ben loved.

It’s obvious that Thomas will be the best judge of what Ben likes. But his mum still has an opinion, based on her assumption about what’s better for Ben in the long run.

We sometimes make assumptions based on our opinions about a customer’s wants and needs. It’s hard to be objective about our ideas when we are invested in the outcome. But that shouldn’t stop us trying to stand in our customer’s shoes for long enough to understand how he feels. Our opinion is immaterial if it doesn’t align with the story the customer believes.

Image by Jonnie Anderson

The Brand Awareness Conundrum

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

Every few months another new restaurant on Bourke Street closes its doors for the last time. Sometimes it’s like watching a car crash happening in slow motion right in front of your eyes. The events leading up to the closure follow a familiar pattern.

There’s the launch day fanfare, accompanied by balloons, the menu reveal and opening offers. The staff member stationed out front hands out leaflets to the hundreds of passers-by trying to entice them in. Many put their head around the restaurant door. Most don’t go inside. A few promise to come back but never do. The sandwich board on the pavement advertising discounted ‘specials’ get bigger and brighter as the days turn into weeks, then months, where too few lunches have been served. Those adverts are a sure sign that the lease won’t be renewed.

Bourke Street is one of the busiest streets in the heart of Melbourne—a place thousands of potential customers walk up and down each day. But setting up shop there does not guarantee that the right customers will come and keep coming. We have come to believe that being known is the key to being successful. That’s not always the case. The people and companies that succeed are not just visible to everyone—they’re resonant with the particular group of people that they have optimised their business to serve.

Back to Bourke Street. There’s a new restaurant that’s quickly become a favourite with busy office workers and weekend shoppers, looking for a quick pit stop and a healthy bite to eat. The first thing the owners did was to design the entrance with empathy. They didn’t want people to feel intimidated to step over the threshold. They wanted to avoid people feeling that they had to commit to sitting down if they walked in—which they believed would stop them coming in at all. They removed the door and left the restaurant completely open to the street. They’re giving people the opportunity to see straight away if this is their kind of place.

Being known by everyone isn’t going to get us to where we want to go. Being right for the right people is where we start. And understanding how to show and tell those customers that we’re right for them is the way we build a sustainable, successful business. We don’t need to find more ways to make everyone see us. We need to find more ways to make the right people sure of us.

Image by Garry Knight

Do You Have A Customer Awareness Strategy?

filed in Marketing, Storytelling, Strategy

The Friday evening tram was jam-packed with commuters, our bodies so closely pressed together you could feel the heat from the passenger standing next to you. As the tram made its way up Collins Street, the people travelling alone avoided eye contact. Two women next to me were chatting about the black jacket the younger one was wearing.

She mentioned the brand name and the store where she’d bought it, then went on to describe why it was ‘worth the investment’. ‘I’m a junior lawyer. I work long hours. I always feel put together when I’m wearing this jacket, even when I’m leaving the office after a twelve-hour-day.’ Sold.

If only the brand’s designer and marketing team had been there to overhear the conversation.

Of course, it’s not always possible to be in the room or on the tram, when our customers have something valuable to share. But it is possible to create a mechanism for hearing and acting on what they tell us. The stories our customers tell—the words they use and the feelings they express are part of our story. We should know and use them. What’s your customer awareness strategy?

Image by Matthew Henry

Why Do Customers Choose You?

filed in Marketing, News, Story Skills, Storytelling, Strategy

What are the top three reasons customers choose you? What story are you giving those customers to tell—not just to recommend you, but to trust and value, prefer and remain loyal to you or your company?

You can make assumptions and best guesses about what’s motivating the people you serve, or you can ask for reasons they will happily share. The stories your customers tell themselves are part of the story you need to tell.

Image by Garry Knight

How To Tell A Story Using The Story Scaffold

filed in Marketing, Story Skills, Storytelling

There’s no question that stories are the best way to engage and persuade people. We have good scientific evidence to prove it. According to neuroeconomist, Professor Paul Zak, ‘Narratives that cause us to pay attention and also involve us emotionally are the stories that move us to action.’ It’s our very makeup, our physiology, that enables us to empathise and to be persuaded by stories. This physiological connection between head and heart is the reason stories work.

Zak goes on to say, ‘Stories that are personal and emotionally compelling engage more of the brain, and thus are better remembered than simply stating a set of facts.’ All compelling stories follow a simple three-act structure, with a beginning, where the scene is set. A middle where something happens. And an ending where we find out what happens as a result of what happened. The sequence of events—what we reveal to the audience, when, is what makes stories work. The goal is to keep the audience wondering what’s going to happen next all the way to the end. When you can’t put a book down, it’s because the author nailed the story structure. The author’s goal is to keep you turning the pages.

Philosophers and scholars like Aristotle, Freytag and Campbell, analysed dramatic structure and gave us story formulas like the hero’s journey to help us become better storytellers. Every successful movie follows these formulas. But they are overly complex for stories we tell every day.

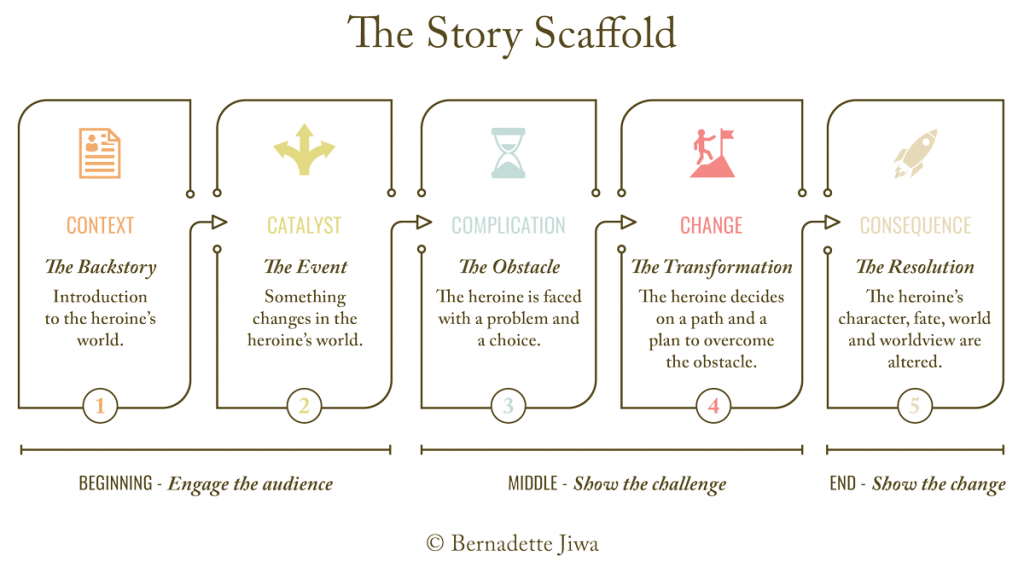

At its simplest, the sequence of events in a story happens in five stages.

The 5C’s of The Story Scaffold

1. CONTEXT

The Backstory

Introduction to the hero’s or heroine’s world.

2. CATALYST

The Event

Something changes in the hero’s or heroine’s world.

3. COMPLICATION

The Obstacle

The hero or heroine is faced with a problem and a choice.

4. CHANGE

The Transformation

The hero or heroine decides on a path and a plan to overcome the obstacle.

5. CONSEQUENCE

The Resolution

The hero’s or heroine’s character, fate, world and worldview are altered.

You can test this structure by mapping it onto any memorable story from Cinderella to Toy Story. Think about what happens in Toy Story when Woody, Andy’s favourite toy is confronted with the arrival of Buzz Lightyear and how he changes throughout the story as a result.

You can use The Story Scaffold to become a better storyteller, not only when you’re marketing but in everyday conversations. Sometimes you will be the hero of the story. But more often when you write persuasive sales and marketing copy, pitch a winning presentation or create great customer experiences, it’s the customer’s or client’s story you’re telling.

Storytelling isn’t just the best way to be seen and heard in a meeting or on a stage. It’s how we engage with people every day by showing that we see them.

If you’d like to practice using The Story Scaffold to tell better stories, consider The Story Skills Workshop.

Image by Carmelody

Signalling

filed in Marketing, Story Skills, Storytelling

According to the Collins English Dictionary, a signal ‘is a gesture, sound, or action which is intended to give a particular message to the person who sees or hears it.’

We are sending signals to our clients and customers whenever they come into contact with our business or brand—even when we’re not face-to-face. Words, images, dress, titles, tone, body language, location, prices, packaging, decor and design give people clues about who we are, what we stand for and what we’re worth. The flipside is that when we allocate resources, we’re also sending a signal to ourselves about what we’re worthy of.

Customers are making decisions based on our signals, so it pays to be intentional about every signal we send. When I get an email, like the one I got yesterday from an insurance company assuring me that my query is important to them ‘and will be replied to within three business days,’ I’m forming an opinion about what it would be like to be a paying customer with an urgent request.

Of course, in the days of online customer reviews, we can’t always control the message—which is all the more reason to make sure that the story we tell when we can is sending the signal we intended to send.

Image by Garry Knight

What The Best Communicators Do

filed in Marketing, Story Skills, Storytelling

Professor Daniel Kahneman has spent a lifetime researching why and how humans make decisions. His decades of work focused on the two ways we think and decide using one of two modes of thought, System 1 and System 2. System 1 makes fast, instinctive and emotional judgements and System 2 operates at a slower more logical level. Kahneman wrote a five hundred page book on the subject titled Thinking Fast and Slow.

Of course, just like us, even Nobel prizewinning researchers don’t usually have a lifetime or five hundred pages to explain the impact of their work. We often only have someone’s attention for seconds, let alone minutes. The mistake we make as communicators, marketers and salespeople is believing that we need to give people all the information while we have their attention—that’s what we were taught at school. We were not penalised for writing down everything we knew in an exam. The best way to win at exams was to write down everything we knew. But this doesn’t work when we’re face-to-face with people.

The goal isn’t just to deliver the information—it’s to capture the imagination. This is how we communicated as children—in stories, not facts. But over the years we’ve unlearned all of that. If we’re serious about making an impact, we need to start reclaiming those innate storytelling skills we once had.

When Professor Kahneman describes how System 1 works, he tells the story about calling his wife Anne on the phone and knowing immediately what kind of mood she’s in just by hearing her tone of voice when she picks up. Whenever he tells that story, the audience laughs, they nod their heads, they immediately get it.

The next time you’re asked a question about what you do or why it works, don’t go into a long explanation. Just start with the words, ‘let me tell you a story’.

Image by Garry Knight